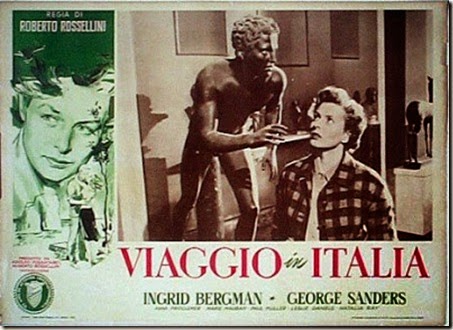

Ingrid Bergman’s “shocking” affair with Italian director Roberto Rossellini was very unfortunate. It wasn’t harmful because they were both married to other people, or that he ran off with another woman seven years after they were married. No, what was unequivocally catastrophic about their affair was that it caused Bergman’s banishmen

For years the Italian-language version of Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy was nowhere to be seen (or heard) in the U.S., and it was originally shown in English. However, quite recently Turner Classic Movies aired the film in its original form (in Italian). Loosely based on Colette’s novel, Duo, the story follows an English couple on their trip to Naples to sell an estate that they’ve recently inherited. Married for m

Did I like Voyage to Italy? Not particularly, but I didn’t dislike it, either. A movie starring Ingrid Bergman would have to be God-awful for me to truly hate it because she’s such a good actress. Still, she doesn’t get to do a lot of acting in this—she spends m

I’m pretty sure that most of the production was shot on location, and in that sense, at least, it has at least one element of Italian neorealism (however, that particular film period ended in 1952). As such, there is an authentic feel to Voyage to Italy—even if its ending is far from realistic. The fact that Rossellini features the Naples’ National Museum of Archaeology, Duomo Cathedral, hypogea (underground tombs) and, of course, Vesuvius and the ruins of Pompeii makes the film much more enjoyable for me. You see, I don’t necessarily agree with Francois Truffaut’s assessment that it’s a masterpiece or that it should be labeled as the first modern film—if you are unfamiliar with the French New Wave, here’s a quick history lesson: Truffaut, Godard, and the rest of the Cashiers du Cinema worshiped Voyage to Italy and, as The Guardian has pointed out, saw the film as “the moment when poetic cinema grew up and became indisputably modern”.

Other than the sights explored by Katharine, the most interesting thing about

![Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17] Seconds - 1966.avi_snapshot_00.20.53_[2012.08.08_23.55.17]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgw7Oc69ZgeOFjpcgI951rdKJmZg-TUi6nO1FHnT0ty0g2MeBfuXWvCreyUU9r1PXRKyCEuAWb9aiaUcjvYQBRhIQ8p-ZE0HKfRmfXarvqn8QwfKZNC5w3jjcDZkX8iH-o-mgxaLC-G3uU/?imgmax=800)