No matter how hard you might try to avoid inserting bias into a documentary you almost always fail. However, that does not disqualify your overarching aim. Such is the case with director Emile de Antonio’s Vietnam War documentary, In the Year of the Pig (1969). When it was initially released in 1968 the war had started to become increasingly unpopular in the United States, and the film only added to the growing anti-war sentiment. What I find most compelling about the documentary is the parallel ‘truths’ that de Antonio exposes. As a student of history, I know all too well that policy does not always conform to reality, and that is the overriding thesis of this timely documentary.

Shot in black and white, the film uses snippets of news footage to visually identify the historical context. While this is a useful tool, it would be w

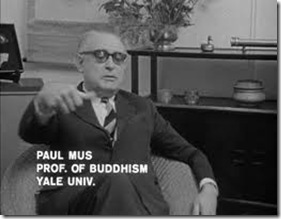

Of these interviews, my favorite is with Paul Mus—he was the perfect candidate to discuss Vietnam. A French scholar who specialized in Far Eastern studies, he grew up in northern Vietnam and was an adviser to General Philippe Leclerc during the reconquest period. de

Overall, In the Year of the Pig is an insightful documentary about the Vietnam question. At times, it is a bit heavy-handed (especially when de Antonio uses American patriotic music ironically or shows American soldiers dead and injured on the battlefield). Still, taken as a whole, I find it to be one of the most well-done and educational documentaries ever made about the Vietnam conflict.