I recently wrote a review of The 39 Steps and based on the comments it elicited I came to the conclusion that Hitchcock’s pre-Hollywood films are often overlooked or even forgotten. I’m sure there are many reasons for this, but I think many of his early British films should be watched to understand how his directorial vision developed. You don’t just wake up one day and direct Notorious or Rear Window. As such, I think Hitchcock’s earlier films provide excellent examples of how he honed his style over a period of many years. Sabotage (1936) is one of those forgotten gems that one should watch to gain more insight into the Hitchcockian vision.

Based on the novel The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad, Sabotage is a suspenseful thriller about an international terrorist group (or saboteurs) who hold London in a state of anxiety through their

The film opens metaphorically with a close-up shot of a flashing light bulb (a warning signal?) and then transitions into a shot of a crowded London street right before a blackout. In true Hitchcockian fashion, the film cuts back to the flashing

Soon we are introduced to Mrs. Verloc’s little brother Stevie (Desmond Tester). Stevie encompasses all that is innocent and good, which is reinforced by his helpfulness and trusting nature. Through

It is really enjoying to watch these two actors play off one another, especially when you throw in Sylvia Sidney as the unassuming wife. In addition, Verloc is the traditional quiet and unassuming Hitchcockian villain. He doesn’t seem particularly menacing (at least until the end of the film) and seems like an inconspicuous

The puzzle pieces start to take shape when Verloc and an accomplice meet at an aquarium and discuss the city’s reaction to the recent bombing. A newspaper headline reads: “London Laughs at Blackout”.

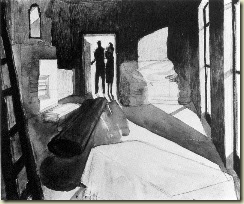

Eventually a plan is put into action to detonate a time bomb at 1:45 on a Saturday afternoon. A note reads: “London must not laugh on Saturday”—yes, the opposite reaction is, of course, the outcome. In a strange twist (but not strange for Hitchcock), Verloc gets Stevie to deliver the bomb, which is disguised in a film reel/roll of Bartholomew the Strangler (a nudge toward the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572?). Ah, but you never send a child to do a man’s work, now do you? Instead of promptly

The film is tension filled, especially little Stevie’s errand from hell and the showdown between husband and wife. The bomb delivery sequence is nearly 10 minutes long and is taut with suspense. The showdown between the Verlocs is rife with unspoken anxiety and edited with shots of uneasy close-ups. In addition, Hitchcock uses

Sabotage is perhaps one of Hitchcock’s darkest films—what with killing an innocent child. It is also one of his few films that doesn’t contain a true mystery. Shortly after the film starts everyone knows who the bomber is and there is nothing to truly unravel. Instead, it is purely a suspense film. As such, it is a rather unique Hitchcock vehicle.

![judy and trolley[1] judy and trolley[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhV2MnsKu4tmGxsYleDRH03fOYrx5m-CqsoEF7uafHgU-Pmdho3Bn6F_uveQ5js6Mlf_ph7DWMjgpqecsAQdOE4NSQ8YRspGwNotSFe28iaqdN6MEKxU6yQsNl_Z7mtsDuLtWRDQ5p5QyA/?imgmax=800)